- Home

- DNR Update

DNR: A Starting Point for Informed Patients & Families

The Center for Patient Protection is a leading voice for patient and family education and improvements related to do-not–resuscitate (DNR) practices.

We provide outreach services to patients and families; help providers design responsive protocols, based on the reported experiences of patients and families, that reduce the risk of harm; and advocate for changes in laws and regulations among governments and healthcare policy makers.

Our extensive research, along with hundreds of cases reported to The Center for Patient Protection, reveals that there are few areas of patient and family engagement that are more open to confusion, risk of medical error and the need for change than hospital DNR practices.

Decisions that can lead to the ending of a life are among the most heart-wrenching any family can be called upon to make. They are all the more troubling when they are made in the absence of the right information. Worse still is when doctors refuse to follow the wishes of the patient or family, or when there is a misinterpretation of those wishes that leads to harm. Yet our extensive research, along with hundreds of cases reported to The Center for Patient Protection, reveals that there are few areas of patient and family engagement that are more open to confusion, risk of medical error and the need for change than hospital DNR practices.

Common DNR Risks & Perils

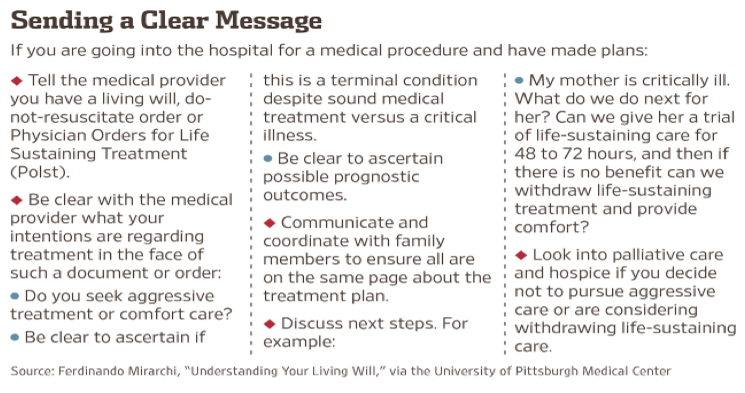

Even when patients present a living will or advance directive indicating their wishes, it is not always possible to contemplate every eventuality or complication that can occur. Just as significant, there is a considerable risk that the intended wishes of the patient will be misinterpreted to the point of harm. This was among the groundbreaking findings of a series of studies known as TRIAD (The Realistic Interpretation of Advance Directives), which concluded that there is “widespread misunderstanding” among clinicians about advance directives.

“We now know that this area represents a nationwide patient safety issue,” according to TRIAD’s lead investigator, Dr. Ferdinando Mirarchi, medical director of the department of emergency medicine at UPMC-Hamot in Erie, Pennsylvania (part of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center system).

A Cautionary DNR Experience

At The Center for Patient Protection’s Online Outreach Clinic, we receive more inquiries and messages of urgent concern about DNR decisions than any other matter. Patients and families know about the widely reported story of Kathleen Finlay, The Center’s founder and CEO, involving her mother’s experiences with DNR practices. They also know that The Center has along advocated significant changes in the way DNR issues are handled, especially in the hospital setting, so that the risk of abuse, medical error and emotional harm can be minimized. Overwhelmingly, the concerns reported to The Center relate to patient or family wishes for full code status being thwarted by the medical team, rather than resuscitation occurring against the wishes of the patient or family.

The Gap in Legal Protection

Some jurisdictions, such as New York State and Ohio, mandate certain DNR practices by statute. In Canada, there are no similar legislated protocols. Some providers, like the Cleveland Clinic, have created their own more detailed DNR protocols that go beyond state-mandated requirements.

But, for the most part, these efforts are inadequate and do not reflect the full commitment to transparency and patient- and family-centered care that is needed. Many of the statutes that do exist, like New York’s, do not “require hospitals to establish mechanisms to enforce the integrity of the informed consent process and hold attending physicians accountable for leading discussions. They also do not specify sanctions for noncompliant individuals,” according to noted DNR researchers.

These weakness continue to produce confusion (for patients and families, and even among clinicians), breakdowns in communications, and unintended adverse events in the clinical setting. They confirm that more needs to be done within state and provincial jurisdictions to set standards regarding DNR disclosure, practices and safeguards. They also show that more providers need to create their own detailed policies based on best practices.

Our Online Outreach Clinic receives more inquiries and concerns about DNR issues and abuses than any other topic.

Recognizing the unique role The Center has played on this subject, over the years world-renowned experts in DNR practices have reached out to Kathleen to explore ways of improving existing DNR protocols, from the perspectives of both providers/clinicians as well as those of patients and families. With a database of more than 2,000 patient and family interactions and personal case experiences, The Center for Patient Protection offers a unique capability that is not found anywhere else in the healthcare system.

The best providers and clinical teams want to know the key information gaps that cause significant barriers to safe DNR decision-making or inadvertently lead to medical error and harm. Patients and families also need help in making informed decisions about their wishes, and about what they need to do in order to ensure the those wishes are being carried out and not disregarded.

The Five Persistent Failures in DNR Practices

The Center for Patient Protection has examined an exhaustive array of cases reported to it, as well as those contained in DNR-related literature and research. When adverse events, medical error or emotional harm has arisen DNR practices involving patients and families, they failure can typically be traced to the following breakdowns.

1 Inexperienced Physicians. Typically, when a hospital seeks consent from a patient or family member for a DNR order, a doctor with limited experience in the early stage of his or her residency is dispatched to obtain the consent. Many have not even examined the patient or know much about their condition. Frequently, these discussions are initiated when families are under extreme stress in unfamiliar surroundings.

Many patients and families report that efforts to obtain consent to a DNR order are conducted in a clumsy and insensitive manner where the patient seems to be regarded as more of a statistic than a loved one with unique human qualities. Families also report what to them appears to be an unseemly rush to obtain such consent and feel overly pressured to agree. For many patients and families, this is often their first experience with the concept of DNR/end of life decisions. Yet this is also where the fewest and least experienced resources are focused, which can easily add to a lack of understanding and trust.

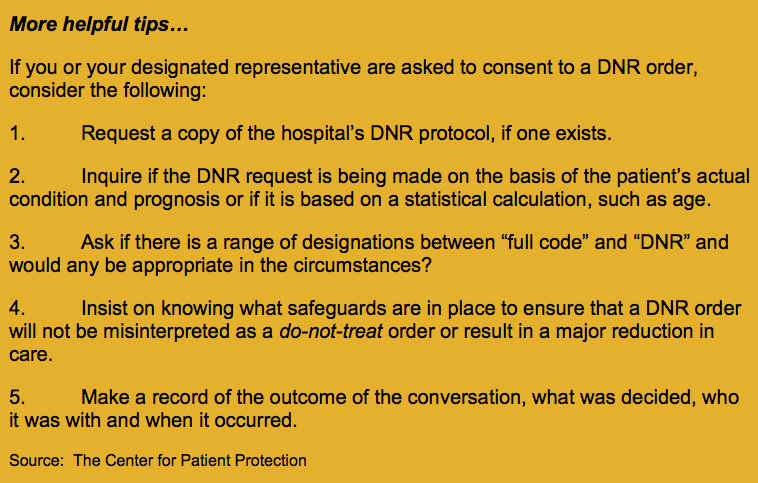

2 Inadequate Information. Research shows that “Many physicians fail to provide adequate information to allow patients or surrogates to make informed decisions and inappropriately extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments.”

Doctors often seek the consent of patients or family substitute decision-makers to a DNR order without providing the full range of information required. For example, it is widely held that there is virtually no success in resuscitating a patient who is over the age of 80. Yet those assertions fail to take account of cases where elderly patients have have survived, such as Kathleen’s then 88-year-old mother, who was resuscitated after a cardiac/respiratory arrest (her condition was charted as asystole at the time).

She continued to improve over succeeding years and today is on the eve of celebrating her 95th birthday, in her home. This story has drawn widespread interest since it was made public in The Huffington Post and, more recently, in Medscape, the online medical journal. . What remains astonishing is that there was so little interest in the medical community in understanding the facts and circumstances that would have allowed this elderly patient, who had already suffered from a brain hemorrhage and hospital-associated pneumonia, to have survived the arrest and recovered to the remarkable extent she did and with significantly enhanced longevity.

Some skepticism is, therefore, appropriate when clinical professionals begin to cite statistics, the veracity and accuracy of which cannot be ascertained by the patient (or substitute decision-maker) and often are not even known by the physician.

3 The Risk of Do-Not-Treat. One of the biggest fears among patients and families is that DNR orders will be interpreted as do-not-treat decisions. This is recognized in the research conducted by Dr. Mirarchi’s team, noted earlier above. research He warns that advance directives and living wills can also produce such unintended results. “The risk is that you don’t receive the necessary and standard-of-care treatment for a critical illness such as a heart attack, which could lead to death or permanent disability, whereas the standard-of-care treatment could save your life.”

This view is dramatically supported by additional research conducted by Drs. Yuen, Reid et al., who caution: “…many providers inappropriately alter treatment plans for patients with a DNR order without discussion with the patient or surrogate. In one survey of 155 medicine and surgery residents, 43% would withhold blood products and 32% would not give antibiotics to a patient with a DNR order. Some believe that diagnostic tests should not be ordered when a patient is DNR.”

In another study, it was shown that nurses would be significantly less likely to perform a variety of monitoring and interventions for DNR patients than for non-DNR patients. Moreover, research of physician preferences and decisions showed that DNR patients were significantly less likely to be transferred to an intensive care unit, to be intubated or receive interventions like the placement of central lines than were non-DNR patients.

In light of the foregoing, it cannot be surprising that one study concluded that patients with DNR orders were 34 times more likely to die in hospital, even adjusting for propensity scores and other covariates.

In a study of ICU deaths involving patients with acute respiratory distress, nine percent of the patients died who were full code, compared with a 97 percent death rate for DNR patients.

Research shows a major risk that a DNR order will be interpreted as do-not-treat and that reductions in care will occur.

Pioneering Law Brings Clarity to DNR Decisions

To address the concerns related to a potential do-not-treat bias for DNR patients, in 1998 Ohio enacted two classes of DNR protocols.

These are set out in Ohio’s law, which is summarized below:

1) DNR Comfort Care

DNR Comfort Care orders (DNRCC) require that only comfort care be administered before, during, or after the time a person’s heart or breathing stops. This type of order is generally regarded as appropriate for a patient with a terminal illness, short life expectancy, or with little chance of surviving CPR.

2) DNR Comfort Care-Arrest

DNR Comfort Care-Arrest orders (DNRCC-Arrest) permit the use of life-saving measures (such as powerful heart or blood pressure medications) before a person’s heart or breathing stops. However, only comfort care may be provided after a person’s heart or breathing stops.

Under this code, the patient’s airways will be suctioned and oxygen can be given.

Under this code, the patient’s airways will be suctioned and oxygen can be given.

These options focus on what will be done for the patient, whereas the conventional, one-size-fits-all, approach to DNR orders centers only on what will not be done (i.e., resuscitative effort). Some see this as more empowering to the patient and more consistent with modern principles of patient autonomy and centered care.

Importantly, early research provides evidence that these two choices ensure a continuum of the most appropriate care and “may help alleviate concern that DNR patients will receive either too much or too little medical care.”

The study aptly concludes that “the simple and vague DNR order should become a thing of the past. Interpretation of DNR orders should not be left to the imagination.”

4 Improperly Obtained DNR Orders | Overriding Family Wishes. There are well-documented cases when doctors have overridden the expressed wishes of the patient or substitute decision-maker and have failed to order resuscitation intervention even in the absence of a DNR order. This practice is a frequent subject of complaint to The Center’s Online Outreach Clinic. Here are two high-profile cases that have been covered in the media. Star article. Guardian article.

Similarly, efforts have been made to obtain DNR consent from patients who clearly have no capacity to give informed consent. In a much published case, Kathleen Finlay, The Center’s founder, tells of the earlier hospitalization of her mother, who was suffering from a serious infection at the time. She had a high fever and was delirious. The family had declined the doctor’s request for a DNR order. He then turned to the patient who had been asleep. “Mrs. Finlay,” he said several times until she awoke, “if your heart stopped beating you wouldn’t want us to hurt you, would you?” Looking perplexed and confused, she said “no” and fell back to sleep. “That’s good enough for me,” the doctor said and signed the DNR order. When the family objected to the manner in which the consent had been obtained, the hospital told them to hire a lawyer if they didn’t like it. It was Christmas Day.

As an aside, this experience also serves as a reminder of how, through their insensitivity and lack of compassion, healthcare providers and medical professionals can inflict avoidable emotional harm on families who are only seeking the best care for a loved one.

Once again, this experience and similar ones reported to The Center emphasize the need for laws that impose tough no-nonsense protocols on hospitals and physicians that specify the manner in which DNR consents can be obtained, the condition of the patient before he or she can provide consent, and the kind of information that must be disclosed in order to preserve the principle of informed consent.

5 Slow Codes. On some reported occasions, a “slow code” has been adopted because the medical team believes resuscitation should not occur, despite the expressed wishes of the patient or family to the contrary. In a slow code response, the expectation of the physicians and nurses involved is that the patient will expire before they arrive to perform resuscitation measures. As a result, they respond slowly to code calls for that patient. Very slowly. In an illuminating article, a nurse of 40 years’ experience enacts the “slow code dawdle.”

According to the University of Washington School of Medicine “The Slow and show codes are ethically problematic. In general, performing slow and show codes undermines the rights of patients to be involved in clinical decisions, is deceptive, and violates the trust that patients have in health care.” providers.

As Dr. Micheal Evans, an emergency-room physician put it in an interview: “It is malpractice. If you’re called to a code, you go. You do it as if it’s a 2-year-old, a 20-year-old or a 100-year-old. It doesn’t matter the age of the person that has an urgent medical need.” Dr. Brian Goldman, a Toronto emergency room physician, calls slow codes deceptive and unethical, noting “it’s hard to find a doctor who hasn’t seen or heard of a slow code being done, if not participate in one.”

Few laws are in place in the United States or Canada to prevent this abuse. Over the years, many families have reported their fear that a loved one was the victim of a slow code procedure.

A Call for Action

All these issues and concerns are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to complications involving DNR practices. These observations are not intended to suggest that there is no appropriate use for properly informed and consented DNR orders in the hospital setting. But it is to strongly give voice to the principle that transparency, compassion, and other hallmarks of patient- and family-centered care must always be present at every stage of the DNR process. In reality, they are absent in far too many instances, based on the reports received at The Center for Patient Protection and on medical literature.

We call on governments and healthcare regulators to ensure that current hospital DNR practices actually protect patients and preserve their rights to give informed consent.

The Center for Patient Protection believes that, in addition to steps governments throughout the United States, Canada and elsewhere need to take to set out safer DNR standards, the healthcare sector needs to seriously review the extent to which current practices fail to protect patients in the context of these often irrevocable decisions, which can be life-and-death determinative. We call upon the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals in the United States, and has set a number of standards for hospitals achieving that status, and the Institute of Medicine, which has a distinguished history of addressing groundbreaking issues, such as medical errors in the hospital setting and, more recently, the risks of diagnostic errors, to conduct a thorough review of current end of life/DNR practices and to develop standards, based on best evidence, to ensure the safe and transparent approach to end of life decision-making, including DNR orders.

A 21st Century Patient and Family DNR Approach

For individual healthcare providers, The Center for Patient Protection has developed a new 21st century patient and family DNR module. With it, we can assist providers in reviewing their current DNR practices with a view to ensuring that they are consistent with the needs of patients and families that are regularly reported to The Center and with the best standards of patient-centered care. We believe this is a practical approach to reducing unintended outcomes and the emotional harm that so often accompanies them.

The Center’s Online Outreach Clinic

The Online Outreach Clinic of The Center for Patient Protection continues to be available through our advocacy services. We also welcome stories from patients and families who wish to contribute to an improved awareness by clinical professionals and others about real-life DNR experiences.

For patients and families who are financially disadvantaged and are looking for guidance on this matter, our pro bono (free) service is occasionally available on a limited basis.

If you are a patient or family looking for more information, or a provider seeking to improve your handling of DNR practices, contact Kathleen Finlay, founder and CEO of The Center for Patient Protection.

Helpful Links:

- A primer from the Merck Manuals on DRN orders

- An article by Dr. Ferdinando Mirarchi on advance directives

- The Mayo Clinic on living wills

- DNR Q and A from Brigham and Women’s Hospital

- Cautionary stories on DNR abuses from the Patients’ Rights Council

- Example of a hospital’s DNR protocol from the Cleveland Clinics